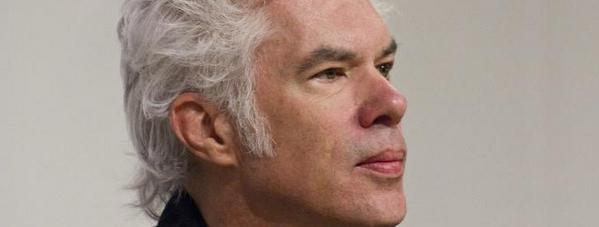

FILM FINANCING: Jim Jarmusch on Vampires, Music and the Future of Independent Film

Jim Jarmusch talks to Indiewire about the future of independent film and his latest film, “Only Lovers Left Alive,” which is now available to watch on Time Warner Cable Movies on Demand as part of their Indie Film Month

Jim Jarmusch is member of that elite (non-existent) club of multi-hyphenate, fiercely independent filmmakers that have covered almost every role in the filmmaking process. Included in this group are the likes of Robert Rodriguez, Julie Delpy and Shane Carruth. For Jarmusch, music has always been a vital part of his creative expression, whether scoring his films, performing with his band, casting musicians in his films or shooting documentaries about them. His latest film “Only Lovers Left Alive,” not only takes the vampire genre back from teenagers with a smart and funny screenplay, but casts one of the lead vampires, Adam (Tom Hiddlestone) as a musician with a penchant for expensive, classic guitars and analogue recording, with Jarmusch performing the guitar parts on the soundtrack.

Interviewed at Thessaloniki Film Festival in Greece, Jarmusch talks about his latest film and the importance of music in his life.

Why did you decide to make a vampire movie? Was it a reaction to those recent teen movies that ignore most of the mythology?

There are so many hundreds of films with vampires in them, but our film is not a horror film. It’s a different kind of vampire film. There are many different not-horror vampire films. One of the most beautiful is “Vampyr” by Carl Dreyer, but there are many others; “The Hunger” from Tony Scott, more recent ones like “Let the Right One In,” which I like very much; Claire Denis made a film called “Trouble Every Day,” Abel Ferrara’s “Addiction,” “Nadja” by Michael Almereyda. There are many vampire films that are not horror movies.

You’ve always been a fiercely independent filmmaker, retaining the rights to your negatives, but not for this one. Is it getting harder now to remain independent?

I love the form so much. Film is such a beautiful form, but it’s getting very difficult – it’s very different to what it was even five years ago – to finance films. I don’t know what to say about that, except to keep going.

Over your career, you have developed the status of being one of the most respected independent filmmakers in world/art-house cinema. Towards the end of the movie, Adam and Eve are watching Yasmine Hamdan singing, and Eve says, “She’s wonderful, she must be really famous.” Adam replies, “I hope not, because she’s too good to be famous.” Is that a reflection of your status?

What I was saying was that I always found more interesting things outside of the mainstream. The things in the margins are more moving to me. Throughout history there has always been a mainstream culture, and a marginal culture, and the most innovative things are in the margins. Not always, but most often.

And where do you see yourself?

I’m most definitely in the margins somewhere. I don’t see myself in the mainstream. There are other people I respect that are much more courageous, and break a lot more rules, that are more marginal than my work.

What’s your view of independent cinema in the U.S. at the moment?

It depends how you define independent cinema. It’s become a kind of marketing tool, especially in America, so I don’t really know what it means. Things have changed, and the worldwide economic crisis, and the new ways of films being distributed, has changed the way they can be financed. I don’t know what the future is, but I know that the new wave of Greek films, using small budgets, is really the future, and maybe the best way. If you look at the history of any art form, let’s just say of rock ‘n’ roll for example, you find that it goes in cycles and there are cycles where, for example, when I was younger we were tired of this big stadium rock ‘n’ roll, this record company, commercial rock ‘n’ roll that was forced on you, in a mainstream way. So it’s very important that, starting, maybe, with “The Stooges,” or the Sex Pistols, or the Ramones; the idea is to reduce down to the essential thing. Don’t worry that you’re not a professional, and this is the future, in a way, where cinema is now. Strip away everything.

I’m much more interested in seeing a film by a Greek filmmaker that made film for $200,000 than I am in seeing “The Great Gatsby” by Baz Luhrmann. That’s just my taste, but cinema needs to be reduced to its essential poetry. It’s a cycle that happens, and we’re in it now, maybe forcibly by worldwide economics, and maybe that’s a very good thing. Already in Greece, Romania, for years now in Iran, there are these beautiful gardens of new cinema that come in places where you would think, “How can they be making films in places the crisis is so severe?” But it’s happening. I’m not a predictor, but I embrace people finding their own way to express themselves. I have a lot of hope for it. You cannot kill these beautiful forms, but you just can’t help them with a lot of money.

The soundtrack to this film is fantastic. Was it influenced by the current resurgence of psychedelic music?

I like lots of different forms of music, so music is really my favorite. I think the strongest thing humans give as expression is music. I don’t know how to exactly define the new psychedelic movement, but there are many bands that I really love that are described this way. I also like drone music, I like trance music, I like the different categories of metal music they call stoner music or doom metal. Some of this I like very much. I also like underground hip hop, and lots of other styles as well. But I do very much like this resurgence of psychedelic music that really transports you and lets you drift, and affects you in a sensual or sensory way. I like heavy rock ‘n’ roll too. But I like lots of different forms of music.

You have your own band, so what do you get out of music that you don’t get out of cinema?

When you make a film, it takes several years. It takes two years to make a film, from writing and financing to shooting and editing. Music is very immediate, so things come out of you very fast. The movie’s composer Jozef van Wissem, he’s a Dutch lutenist, and I made a few records together last year, and my band SQÜRL, which is Carter Logan, myself and Shane Stoneback, and now Jozef when we play live, we made all the other music in the film, around Jozef’s lute music. All the guitar music in the film is my guitar playing, which is very droney and not really a virtuoso style of music.

As a filmmaker and musician, what comes first, the image or the sound?

Neither. What usually comes first is some characters and some places. I’m imagining a world to create, so I think of the places where I want the film set, and at the same time I think of the central characters, so it’s neither of those things first. The image and the sound are very much the same thing to me as they create the atmosphere. Film is the most closely related form to music because film passes before you in its own time. It has an internal rhythm, it is edited and has shifts and movements. It has slow parts and fast parts; quiet parts, loud parts. They’re very intertwined for me. I try to learn about filmmaking from music, and I think of music in terms of cinema. I’m confused, but happily confused.

As a New Yorker and musician, you must have been saddened by the recent death of Lou Reed.

I’ve lived in New York for a long time and Lou Reed is kind of like our godfather of rock ‘n’ roll. Lou Reed and The Velvets were groundbreaking, and at the time when Velvet Underground first began, people hated it and thought it was noise and not even music, and now you see how pervasive the inspiration and influence of The Velvet Underground and, of course, Lou Reed have been. In New York it is truly a great loss to lose Lou. But we don’t lose him because he gave us so many amazing things. We weren’t close friends, but I knew him, I got to hang out with him and had dinner with him a few times, and spent time talking with him. He was, for me, a huge inspiration. So I say, long live Lou Reed.

In one of your rules of filmmaking you say, “Nothing is original. Steal from anywhere that resonates with inspiration or fuels your imagination.” Where did you steal from for this new movie?

I’ve probably stolen from all kinds of places, but not really consciously. There’s nothing in this film that I can consciously say that I was making a direct reference to a film, but just the things they mention and talk about in the film as inspirations for the characters are then inspirations for the film itself. I don’t know if steal was really the best word to use, whenever I wrote that, but my intention was that there really aren’t original ideas. The beauty of ideas is that they are like waves in the ocean and they connect with things that came before them, and I think it is very important to embrace things that interest you and influence you, and incorporate them into what you do, as all artists have always done. The ones that say they don’t, are lying. Or are afraid that their work won’t be seen as being original, somehow.

Why did you choose Tangier and Detroit to set the film? Was it for Tangier’s multiculturalism that had attracted great writers before, and because Detroit is a now a symbol of Western industrial decay?

I’m not very analytical. I don’t want to talk about the symbolism of these cities because it’s in the film. What they mean, I place in the film, and I don’t really feel so comfortable explaining it. I felt they were appropriate places to help define these characters. This is not really a vampire film, or a horror film, it’s a love story and character study, so the places where they live become very important in defining them. It is important that they are vampires because that allows them to have an overview of history over hundreds of years, which is part of the story as well. Also, I love Detroit and I love Tangier very much, so part of it was my wanting to spend time there. Both of these cities have many qualities and I could talk for hours about why I like them and what they mean in the film, but I prefer not to.

“Dead Man” was a film about mortality, and “Only Lovers” is a film about immortality. Is age changing your perspective about life?

I don’t think so. For me, “Dead Man” is about life and death being something circular; being the same thing, in a way. This film is about, and I’m not good about analyzing my films – I don’t really want to know what it is about exactly – but it’s sort of mysterious to me. I hope part of it is to celebrate our gift of being conscious, because if you look at this planet Earth, and life on this Earth, and how strange and unusual that is, and in the expanse of the universe, life on Earth is just tiny little flicker. And yet, we’re in the middle of it and we’re given this consciousness of being alive and being human beings. I even think that one idea that is in “Only Lovers Left Alive” is to celebrate this consciousness. The character of Eve is very strong about that. Adam is a little weaker about that, and a little more romantic, and gets disillusioned by human behavior, which I do as well. I hope the idea is to celebrate consciousness, life and being alive. At the same time, I don’t think I would want to be alive forever, because death is part of a cycle, but I’d like to live a lot longer.

With the characters’ long history, do you see the film as a sort of time capsule?

I think that would be a bit presumptuous to think of it as a kind of time capsule. In this film there are many references to other artists, to science, to other things that are very important to me, but I think that if I can make a film and I make a reference to some things – there’s mention of William Blake in a film I make, and there’s someone in Kansas, or someone in Lithuania, who sees my film and they don’t know about William Blake and they are interested, then I feel that we’ve accomplished something with the film. I can’t think of it in such a broad way, but if even one person is inspired to investigate something from the film then I am extremely happy that something of interest was passed on to someone else. That is my largest hope.

And in this new film there are a lot of mentions of Nikola Tesla. Is this because not enough people know of his genius? And do you find it ironic that the Detroit motor industry killed off his idea for an electric car, and now the city is in decay, even if his name lives on as an electric car brand?

There are a lot of ironic things about Tesla. The things Tesla gave us are almost impossible to list. We wouldn’t have wireless microphones, we wouldn’t have alternating electric current, or this type of illumination. We wouldn’t have most things we take for granted, which came from Tesla’s imagination. In the end, Tesla was discredited. He was treated like a madman. He was exploited, and they stole things from him. Ultimately, he was not given respect, and yet he changed the way we live in every way. I find this very odd and unfortunate, but the main reason we should remember that Tesla was discredited was because his real concerns were free energy for everyone, and he wanted to find ways that would make warfare basically impossible, using shields based on particle acceleration – or what they called a death ray. Tesla wanted no war and he wanted free energy. This is because of the now-present corporate, almost crypto-fascism, in the world, these things are denied to us, and yet they are fully possible. We don’t have to use these kinds of fossil burning vehicles. There are many alternatives. We don’t have to pay corporations for this energy. There are other ways this could happen, but the small percentage that control all this wealth are basically corporate and they have decided for us. So we should remember what Tesla wanted for us, and then look at what we have. There is a big question of why it is this way, instead of the other way. He’s very important to all us, for how we live, but also his ideas and ideals are very valuable, and they’ve been exploited and tend to be forgotten. But he won’t be forgotten. I hope.

Culled from INDIEWIRE

Daydreamers Official Trailer by Timothy Linh Bui: Released by Dark Star Pictures

Daydreamers Vietnamese Vampire Thriller – May 2nd release

Afternooner by The Harrow Brothers: Funniest Movie of the Decade on VOD & DVD April

Freestyle Acquires “Afternooner” for April Release

Where We Stay by Florence Bouvy to Screen at CIFF

Where We Stay | CIFF Selected Drama About Friends Hiding Unspoken Truths