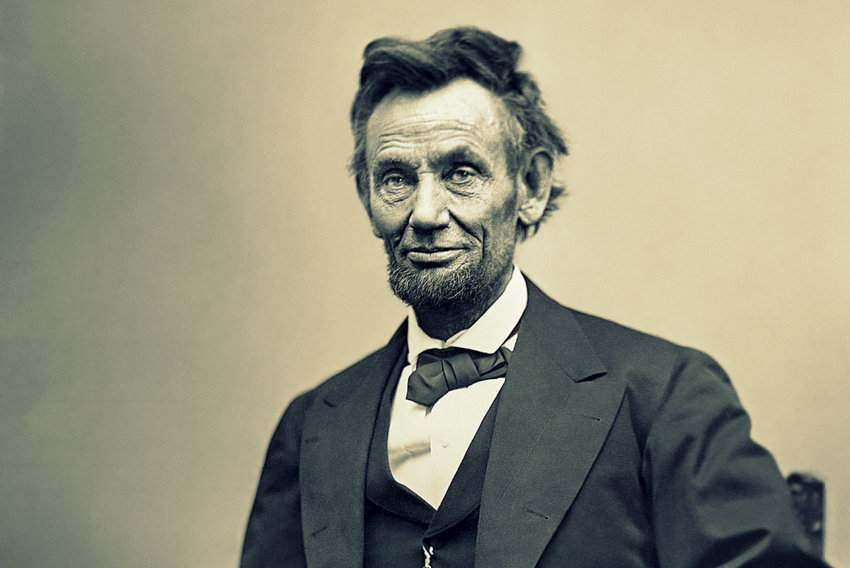

If you are writing about Abraham Lincoln, he was born on a certain day and assassinated on another.

Director Amy Glazer Brings Kepler’s Dream to Life

An 11 year old searches for a missing rare book from her grandmother’s library

How I Made My Film, ‘Fear, Love & Agoraphobia’ by Alexander D’Lerma

A Step by Step Filmmaking Process of Fear, Love & Agoraphobia

Abraham Lincoln is our case study in fictional writing. Unwritten rules are made to be broken. However, there are certain things that one can’t do. If you are writing about Abraham Lincoln, he was born on a certain day and assassinated on another. Abraham Lincoln delivered his Gettysburg Address and either the sun was shining or it wasn’t. Those are facts. The history of the Civil War is more or less fixed. You can’t have him riding in a car or wearing pants with a modern zipper. He cannot smell of Brylcreem, which wasn’t created until 1928.

But historical fiction is in no way a textbook. What was Abraham Lincoln thinking and feeling as he took the stage to deliver that famous address? How had his mother’s death affected him? His son Willie’s? Those require fictional leaps, even if you can access all Lincoln correspondence and personal diaries.

Many novelists — and filmmakers all the way up to Steven Spielberg’s

Abraham Lincoln — have attempted to see the man in full, generally reflecting their own times as much as his. We need heroes. We need to tear down the statues of heroes.

In the case of Abraham Lincoln, it has been noted that he was possibly homosexual or had physical relations with men. Gay was not a word at the time. C. A. Tripp’s thought-provoking nonfiction scholarly book The Intimate World of Abraham Lincoln makes a compelling and provocative case that Abraham Lincoln had intimate relations with men. it names names. It identifies his early entry to puberty as a possible explanation, if not cause. It cites his bawdy humor, with jokes so dirty they were often not recorded.

So, in that case, if we were to write historical fiction about those elements, or include them in a book about a character who encounters Lincoln in The White House, there would be room to speculate with fiction. Who was the man really? What were his dreams? His sorrows? His true affections? His feelings towards his wife Mary Todd Abraham Lincoln, the mother of his beloved children?

So, in this example, I hope to have explained that there are factual signposts and there are fictional leaps. As a writer of historical fiction, one has to make choices to move from one known event to the next. We are not biographers who must stick only to the facts as known. And, even those, are subject to the debate of historians themselves.

And this fluidity of the past is even more the case in fiction where the subject isn’t as well-documented as Lincoln, when writing stories of the underclass, people of color and women. We must be lions in giving voice to the voiceless, following the African proverb: “Until the lion learns how to write, every story will glorify the hunter.”

If you like what you read, please follow Thelma Adams on Amazon.