Nicola Rose is a filmmaker, puppeteer and now contributor on indieactivity. She will be writing periodically on puppetry in independent film. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram

Puppets are wonderfully giving artistic instruments. They mold to the personality and talents of those who inhabit them, as does the art of puppetry to those who adopt it. And “adopt” is often an apt word, as puppetry is rarely the first art a puppeteer comes to – rather, something new taken up along the way, then kept for good. UK-based puppeteer Jeremy Bidgood is no exception, having come to puppets through the graphic arts. Fitting, then, that Bidgood should find his niche in shadow puppetry – a highly visual sector of the art as well-adapted to comedy as to beauty or darkness.

To wit: this writer first came to Bidgood’s work via a chance viewing of his shadow-puppet setting of Schubert’s “Erlkönig” – an admirable showcase of Bidgood’s precision and musicality. Meanwhile, Bidgood’s humor takes center stage in his work with Lewis Young on the comedy show The Great Puppet Horn. We had a chance to speak to Bidgood about his art, considerable range, and the synthesis of puppetry and animation.

Tell us about your background in puppetry.

Bidgood: Like many others I came to puppetry by a slight roundabout route. I was studying Fine Art in Edinburgh making sculptures, installations and some mad performance work. I was also heavily involved in the very lively student theatre scene acting, directing and designing. During my time at art college I increasingly found the more fanciful dialogue surrounding the fine art world frustrating and became less interested in making gallery work where I was always removed from the audience. Live performance, especially the relationship between the performer and audience started to fascinate me and at some point in playing around with all this I discovered puppetry which neatly seemed to marry my sculptural and performance interests neatly. My first experiments were not good. I knew nothing about making or performing puppets but over time I started to meet other puppeteers, see more work that inspired me and learn what materials are appropriate and what materials are really really inappropriate for puppetry (one of my earliest attempts involved plaster of Paris believe it or not…)

Which came first to you, puppetry or film? How did you end up combining the two?

Bidgood: Film, but only just and only in very specific contexts. I initially gained a grounding in film at art college where I was making films for projection-based installations. I’ve always loved technical processes. Initially this manifested itself in sculptural processes like mould making and casting but film soon fed this urge. I love the whole planning, setup, shoot and then the edit. Actually the edit is usually horrible and done with the clock ticking but there is something fun about that too.

That last bit especially resonates. Now what is it about shadow puppetry that speaks to you in particular?

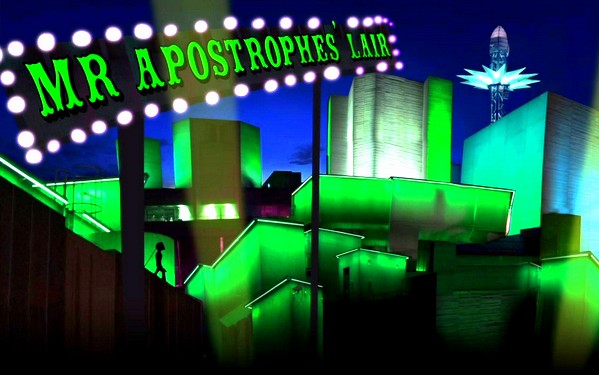

Bidgood: It’s beautiful (or at least other people’s shadow puppetry is beautiful, mine tends to be more ridiculous than beautiful!). It’s also really stupid and throwaway – it’s just some cardboard stuck to sticks. We like to throw the puppets about on stage when we’re done with them to disrupt the slightly extreme reverence that puppets sometimes have. Although sometimes my blister covered fingers wish we could treat the puppets a bit more carefully to save on the cutting out! Shadow puppetry also has a shared language with film and animation. When Lewis (who collaborates with me on The Great Puppet Horn) and I first started talking about working together shadow puppetry seemed a good place to start. Lewis is an animator and I’m a puppeteer and we wanted to make something that combined out interests and was like a live version of our favourite animated shows. The puppet geek in me also loves the history of shadow puppets being used for satire and subversion. Paul Zaloom’s show The Mother of All Enemies introduced me to the madness of Karagoz, which I rather like.

You created a wonderful shadow puppetry piece set to Schubert’s “Erlkönig.” What was the genesis of this piece?

Bidgood: This was a commission for the Oxford Lieder Festival. I am no classical music buff and have little to no knowledge of lieder but I loved working on this – Erlkönig is such an expressive and creepy piece and Sholto and Dan’s recording is beautiful. I was really drawn in by the darkness of Goethe’s story and the really expressive rhythmical nature of Schubert’s music. The Festival were great and very trusting and allowed me a lot of creative freedom to do what I wanted. Whilst the original story is wonderful I really wanted to link the video directly to the Lieder Festival hence interweaving the performance footage with the narrative. Doing the hands for the piano player was particularly fun.

Let’s talk about the synthesis of puppetry and music. To you, what does the one art bring out in the other (and vice versa)?

Bidgood: Humm… I think rhythm as a compositional device links the two very neatly. I certainly found the rhythm of Erlkönig really inspirational when I was thinking about the puppets and also the edit. Music can also be so graceful and movement focused just like puppetry. Oh and of course both are so driven by breath. There’s a lovely video of Adrian and Basil from Handspring Puppet Company taking about music and breath in their show Or You Could Kiss Me that they made with the National Theatre in London. They were using the breath of the accordion to partially represent the last aching breaths of their fictitious older selves near death. Beautiful stuff.

At the other end of the spectrum, what do you think makes puppets ideal agents of comedy?

Bidgood: Puppetry is by nature quite ridiculous. However you dress it up, it’s adults playing with dolls or toys. Don’t get me wrong I think this is an excellent thing and more adults should do it – playing with toys that is. Playing can be such a creative release and inspirational. It’s also fun. So yes puppets are by nature ridiculous (it’s also partly due to scale – they are comically small or large) They can also say and do things we can’t a lot of the time and we can do things to them we could never do to human performers without the show getting really really really dark. Having said all this puppetry can also beautiful and affecting, it’s such a versatile medium!

How did “The Great Puppet Horn” come about?

Bidgood: As I said above, Lewis and I were talking about potential projects we could do and wanted to make a live show that brought together his interests in animation and mine in puppetry. We both have some experience of each others worlds as well. I’ve done bits of animations (mainly stop motion) and Lew has worked with me on other puppet productions. So, there was a mutual respect and understanding of each others worlds. Puppet Horn was us trying to make a live animated show (of sorts). I love animation but find the process so so slow. It’s like really stoned puppetry. With live manipulation you can get a scene done so much faster, which is useful if you want to make satirical content that may have a short shelf life. We have spent hours creating content that we have only performed a handful of times because it was so ‘of the moment’ and a month later already felt old. That’s a battle we’ve always had with Puppet Horn – on one level it is cheap and easy to make (card on sticks) on another level the show is never finished and constantly needs updating. But that is part of the fun!

Who are your collaborators and colleagues, and how did you find one another?

Bidgood: I collaborate with all sorts of people both through my company Pangolin’s Teatime and as a freelancer. Much of it is on a project by project basis, which is always really exciting – getting to work with new people. Obviously Lewis has been a regular collaborator for a while and there are a few other friends and colleagues who reappear in multiple projects. However, as with many artists there is quite a lot of solo work as well. The Erlkönig video, for example, was me flying solo (although I did work with Sholto from the Festival to some extent in the planning of the film).

Who do you hope to reach in your work?

Bidgood: Smug urban liberals like me… I joke but to some extent there is always that worry – that we make work for a bubble. It’s something I worry about with Puppet Horn. Obviously we have a particular political and social leaning and the work reflects that and that alienates some people. We’ve done some random gigs in the middle of the British countryside to rural audiences and they laughed but they clearly didn’t interface with all the content that well and there were definitely some lines crossed. There’s actually a rural touring network in the UK who came to see a show we were doing at the Edinburgh Fringe once. They decided pretty quickly that we weren’t going to sit well with their target audience… But that’s fine. I always love the random collection of people who come to our shows. We also have a problem with people bringing kids. Not that we aren’t happy to have kids in the audience (and when the come they seem to really enjoy it) but parents often think puppet equals child friendly (despite warnings otherwise) and then get all huffy when we say the naughty words. Sometimes the parents are very relaxed though (smug urban liberals of course!).

What is next for you?

Bidgood: Puppet Horn is developing some new work after a bit of a break. Both Lewis and I have had our first child in the last year (technically our partners did the having but we both are playing supporting roles). So its been great to spend some time with the little ones. However, we’re both itching to do some more Puppet Horn so watch this space as they say!

news

Richard Green Documentary, ‘I Know Catherine, The Log Lady’: Premiere in NYC, LA May 9th

Lynchian Doc I Know Catherine, The Log Lady Makes Hollywood Premiere 4/17, Rollout to Follow

In Camera by Naqqash Khlalid Launch on VOD April 29

Naqqash Khlalid’s Directs Nabhan Rizwan. In Camera stars an EE BAFTA Rising Star Award Nominee.