I was born in Germany in 1979 by chance when my brother was treated there for his illness. I was just a few months old when my mother had to go back home and my father stayed in Germany. I have 5 other brothers with whom I have lived together in Germany since 1986. I originally come from a Kurdish town Dersim in eastern Turkey. Political issues and experiences have always been pre-programmed for us.

That must be the reason why I make socially critical and political films today. I only discovered the passion of filmmaking about 8 years ago. I made my first short film in 2014, which was followed by 4 more. As a director, I am driven by topics that touch and interest me. My way of working was very naïve and untouched in the beginning. I did a lot of things intuitively, because I didn’t go the classical way via film school. Now it’s a mixture of professionalism and intuition.

indieactivity: How do you choose a project to direct?

Cengiz Akaygun (CA): I’ve written and directed all my own films so far. The ideas come out of the moment. If they touch me and I feel they have potential, I get behind them. But I’m always looking for stories that have a form or a way of telling them that people haven’t heard before. I’m moved by deep stories where the viewer can see different levels. And where he can pick out his truth. I want to tell stories that move but do not explain too much or transfigure.

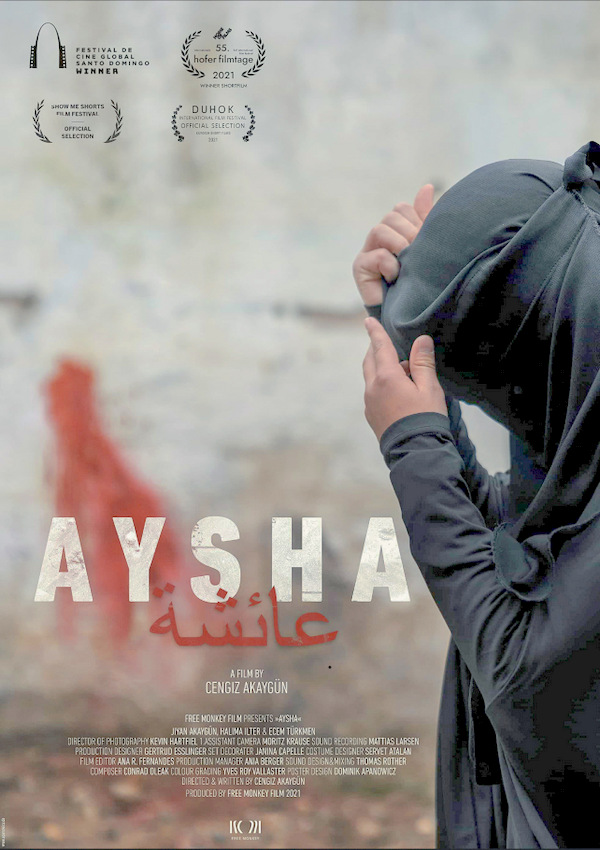

Watch Official Trailer for AYSHA directed by Cengiz Akagun

Why filmmaking and screenwriting? Why did you get into it?

Cengiz Akaygun (CA): I think it’s like someone who discovers an instrument for himself. And once he understands that he can do it, you can’t stop. To see those lines turn into images and move is great. In music it’s the notes and in filmmaking it’s the dramaturgy, with all the twists and turns that create the tension and get the audience emotionally involved. I think the melodies of my stories have always been bubbling inside me. Now I have found a medium and a way to tell them.

How can a filmmaker distribute a film? How do you get it in front of an audience?

Cengiz Akaygun (CA): I think the best way is to find a distributor or a sales agent. You can’t do everything yourself. And it’s good to have collaborators. Even if sometimes you have less of them. It doesn’t just look more professional, it is more professional. Because that way you have more time to take care of other things. With a short film, that’s more difficult, which I think is a shame. But I think the short film is a very valuable format. There should be more offers and opportunities here. Otherwise it’s damn difficult when the artist has to market it himself.

Is there anything about the making of independent film business you still struggle with?

Cengiz Akaygun (CA): Independent filmmaking is always a difficult path. I’ve produced all my films on a low budget and under difficult conditions. But that always has its price. Film funding doesn’t always encourage you, but they sometimes challenge you. They tell you that your film is not eligible. Then it depends on what you mean by that.

The first feeling is always discouraging and you think all is lost. But then I remember that it’s only some people who choose films according to their taste. So I have to find another way to make this film with little resources. I still have difficulties with the fact that films are produced in Germany under certain conditions and dependencies. When a film is to be produced, they look to see if a broadcaster is on board, who the producers are, and what funding is already on board.

And also whether it’s a well-known director. It should primarily be about the story and whether or not you want to give the person who has put so much time and work into it a chance. Unfortunately, a lot of the industry is about relationships. But hey, whatever. But I want to encourage those who are going down the same path as me and take this opportunity to tell them that my film has now been submitted to the OSCARs without a dime of funding and is on the longlist.

The day will come when the we will also become visible to the funding agencies. Because at some point, diligence pays off.

Talk to us about your concept on collaboration?

Cengiz Akaygun (CA): I usually look for people who fit me and my way of working. A mixture of professional filmmakers from the industry, film students, professional actors and supporters from outside the industry make up the majority of the people I work with. But also in the meantime a professional distributor who sells my film and production companies who are interested in working with me.

What uniqueness do female directors/filmmakers bring to film/tv/cinema?

Cengiz Akaygun (CA): In my opinion, uniqueness always lies in one’s own signature and personality. This then shows in one’s own work. A director should always have a relationship with the material and vice versa, the material should have a relationship with the director. That automatically makes the work unique.

I believe good and unique directors enrich us with films that give us access to undiscovered worlds. A signature includes not only technical skill, but also a narrative form that can be unique, because this form also includes a touch that only the director, the director and the writer can give us. So a story should not be realized by just anyone. It has to be in the right hands. That is my conviction. I make no distinction between female and male directors. In the end, what counts is the work and the work that finds its audience. But of course women also have a completely different approach to certain topics, which can also be enriching and enlightening for society.

When you are offered a project, what things do you put in place to deliver a good job?

Cengiz Akaygun (CA): I first check whether I like the project and whether it suits me. Because I’m only prepared to invest a lot of time and energy in something I find good. Then it can only be good. So I automatically deliver a good job.

How do you find the process of filmmaking as an indie filmmaker?

Cengiz Akaygun (CA): I think it has its difficult sides, I already mentioned those. But it also has something good. The fact that you have to do so much yourself and have to deal with so many difficulties. You learn a lot and you become more confident in your work. Many get tired and give up the fight. I can understand that. Especially because you have many other obligations in life that are connected with costs. There is a system that works against you for a while but after a while you can’t look away. That’s why, for me, independent filmmaking is also a way to get there. No matter how the film market works, it will have to recognize and reward your work. Even if you made it without their money and dependencies.

Why would you choose an actor, writer or producer? What are you looking for?

Cengiz Akaygun (CA): Simple. If they understand the story, fit the story and me, and stand behind it. To the bitter end. I also don’t look at how famous someone is or how big a production company is. It’s more about whether they have the fire and desire to give their best to the film. Because that’s the only way you get the feeling that you’re in the same boat.

At what period in the filmmaking process, do you need to start planning for distribution?

Cengiz Akaygun (CA): Usually when the film is completed. But it is smarter to start before that. Because I think a good distributor can also help with the release of the film and the way of release. By that, I mean to place the film correctly in order to be more successful in sales later on.

Indie filmmaking is a model of small budget. How do you get a film to the audience budget?

Cengiz Akaygun (CA): It’s the same way as with a big budget film. I think the paths are clear. But it’s more difficult and the hurdles are bigger if you don’t have a distributor. That’s why it’s important to achieve a certain success with the film at festivals. That’s how you attract the attention of sales companies and distributors. Why shouldn’t they buy a film that is successful and celebrated by the audience? That’s what it’s all about. And if you are very successful, you might even be in a position where you can choose the distributor.

How do you think filmmakers can finance their projects?

Cengiz Akaygun (CA): The classic way is to try different film funding and broadcasters. Then there is the crowdfunding route. Or non-profits and cultural associations that fund film. Now there are also the streaming providers that like Netflix and co. Of course, you can also sell your car or your house but I don’t recommend that. But I think even if all ways fail, there are so many possibilities to make a film in our digitized times. A simple camera, a small team and a strong story that doesn’t need spaceships can do it. As the saying goes. Necessity is the mother of invention.

Describe your most recent work, or film, take us through pre, production and post production?

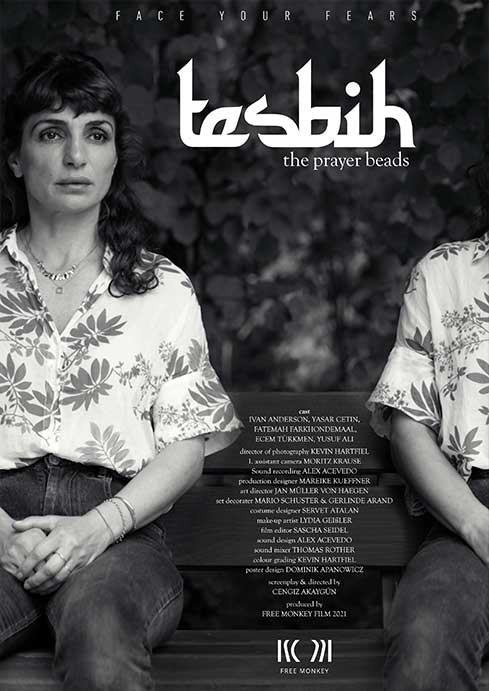

CA: I had already finished writing the script of AYHSA in 2020 and was looking for a suitable location. At first I even wanted to shoot in Iran, but decided against it because of the political situation and the dangers. Then there was the question of whether to shoot in Turkey. But in the end it was too much of a hassle because of the logistics and the costs. The middle way was Naples. I had found an earthquake city that was completely destroyed by an earthquake in the 60s and would have made a good setting. We had prepared everything, even the location. But then Corona came and we couldn’t leave and couldn’t do anything for over half a year. In the meantime I shot a semi-experimental film >>TESBIH<< completely without dialogue.

But my fingers were itching. I wanted to shoot AYSHA. So I decided to build the SET and shoot it in Germany. I reduced the set, which was about a house on a street, to a backyard cut off from the outside world. So the backyard became the window of a big serious theme. I found a demolition company that had a house that was about to be destroyed. So we were allowed to do what we wanted with it beforehand. This is where my great set designer Gertrud Esslinger came in. With the help of her assistant Janina Cappelle and other helping hands from the demolition company, she managed to realise the concept I wanted from her for the realisation. So we already had the set. I had already set up my cast.

With that, we already had the set. I had already set up my cast. The children were already in my environment, the child who played AYSHA was Jiyan Akaygün. He is my brother’s child. The other child who played the sister was Ecem Türkmen. I had worked with her four years earlier on another film. The only professional actress was Halima Ilter.

Nevertheless, she met the children at eye level and it became a good collaboration. It was not easy for the children to work with such a professional actress. But the children got better with every take. It was equally important for us to tell the set and the story as realistically as possible on the visual level.

Therefore, we had to make sure that we always kept the camera at a certain angle. One cm further up and we were back in Germany. I’m glad that I had my cinematographer Kevin Hartfiel by my side, with whom I also shot TESBIH. We already got along very well on the story level and the preparations and always looked for a translation of the story written in text on the picture level. We then agreed on a language that narrates the Middle East but remains true to a universally valid visual language in this backyard. This should not appear too exaggeratedly desert-like, the light should be very minimalistic and the images should reflect the realism and the closeness to the characters.

I think we managed that well in the short time we had. In the end, we only shot with children for three days. Since they were children, we could only shoot half days at a time. But thanks to good preparation, we managed to finish the film. Our production manager Ania Berger always kept an eye on the time and made sure that everything ran smoothly in the background. It is very important that there is a good atmosphere on the set.

Authenticity is not limited to the set and to the play. The costumes were also important. Everything that was seen in the film must be believed by the viewer. If he doesn’t, we’ve already lost. With this in mind, I approached the matter and discussed the details with the various departments. The costume design also played a big role. This described the appearance of the characters and their effect on the audience. I had discussed a lot with my costume designer Servet Atalan in advance and also ordered several fabrics and alternative dresses. Nevertheless, she took her sewing machine with her to the set to be able to make small changes on the spot. That worked out very well.

In post-production, the budget was very limited and I had to do a lot of pre-production work. Especially with the editing as well. Here I did a lot of pre-work and pre-screening and told our editor Anna R. Fernandes exactly which takes were good and which one she should take. This made the editing process quite clear and short. I also stayed true to the script and the chronology in the editing.

I also did a lot of advance work for the sound design. It was about telling the war on the sound level. To do this, I brought our sound designer Thomas Rother on board, who then conjured up the great Foley’s and with whom I sat very often in the studio until we finally agreed on a common result.

What is your experience working on the story, the screenplay, the production, premiere and the marketing?

CA: Especially with Aysha, my last film. I have to say that I was lucky that for me the beginning and the end were clear. For me, that is the parenthesis of the story into which I then insert the various acts, twists and turns. But I also got a lot of feedback to be sure that the story also ignites and arrives. The production itself I have completely taken over. Since there was no funding, that was difficult. The premiere in Germany went very well. We won the short film award at our first German premiere at one of the most important festivals in Germany. It was the International Hof Film Festival.

How did you put the crew and cast together? Did you start writing with a known cast? What was your rehearsal process and period?

CA: I worked with a team and a cast that I was already partly familiar with. The kids in my film were amateur actors that I also knew. One of them was my brother’s child and the other was the daughter of a friend. They were in close proximity. This had the great advantage that I could rehearse the text several times beforehand. The only known and professional actress was Halima Ilter. She got along very well with the children. I did more text and position rehearsals to be able to estimate the positions and the ways for me. So I could think more about alternatives and see what works and what does not. Too much rehearsal can sometimes take the tension out. That’s what makes it exciting on the set. Waiting for the moment and hoping they make it or seeing what they offer.

What and how long did it take to complete the script?

CA: It took c.a 2-3 months in total with all the changes. But with intervals because I kept coming back to it to look at it from a distance. I wrote it alone.

Did the tight shooting schedule make it harder or easier? How did it affect performances?

CA: We had a tight shooting schedule. Three shooting days in total. But in return, a resolution that was doable in the time. I consistently decided on a resolution before the shoot because I knew there would be children on set. I had to save time everywhere I could.

Since the film basically feels like a scene that we could play out in one piece, I just wanted to let the kids warm up. Then when they were warm, it took fewer and fewer takes. Halima Ilter was also a great motivator for the kids. They had to keep up with her, which was a little more difficult for the kids at first. Because she made the children feel insecure at the beginning with her excellent playing. Until they realized the seriousness of the situation. That in turn brought tension into the room. I knew the children and worked with subtexts, which Jiyan, for example, who played Aysha, internalized at some point. I then only had to work on subtleties. Everything else eventually worked.

How much did you go over budget? If you did, how did you manage it?

CA: I managed to do it roughly within what I had envisioned. I had to work a lot with reserves and partial payments, and I also got the catering and equipment partially sponsored. In that respect, I was very lucky. But unfortunately, the costs never stop. Even after completion, a lot of money and time goes into the exploitation, festivals and promotion of the film. But I think that’s part of it.

Watch Official Trailer for The Mandarin Tree directed by Cengiz Akaygun

When did you form your production company-what was the original motivation for its formation?

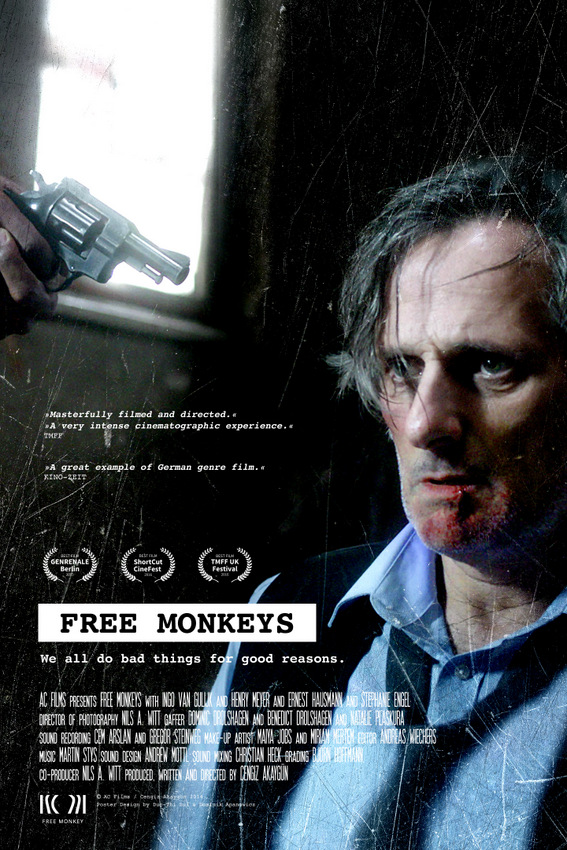

CA: I think that was 2012. The motivation was to gain experience. The first few years I shot images and commercials for companies. But that didn’t really fulfil me. In 2014, I had an idea for a short film called Free Monkeys. The film was very successful at many festivals. In 2016 I founded Free Monkey Film. Since then I produce my films under the name Free Monkey Film.

What other films have you written and made?

CA: Free Monkeys (2014), The Barber (2016), The Mandarin Tree (2018), Tesbih (2021), and Aysha (2021).

What do you hope audiences will get from the presentation of your film?

CA: At best, I hope that the film dramaturgically with all its surprises and twists will take the audience on an emotional journey without them losing interest and getting bored. If the film is remembered by viewers as a good film. Then I have achieved something great.

What are your future goals?

CA: I would like to tell important stories in my lifetime because they are close to my heart. There is so much to tell and hopefully I will have the opportunity to make many more films and learn so much more. Because I believe that we never stop learning.

Tell us about what you think indie filmmaker need in today’s world of filmmaking?

CA: We need courageous producers. We need actors and filmmakers who continue to believe in independent filmmaking. Because I believe that sometimes, especially with small budgets and small opportunities, great ideas and forces can emerge that should not be underestimated. I’ve seen films made with 2 million euros that looked like nothing. And I have seen films that were made with 2,000 euros and were almost a masterpiece compared to the more expensive film. We need brave new minds in the industry. Above all, we need diversity that is also visible among the decision-makers in the industry.

What else have you got in the works?

CA: I’m currently working on a feature film script that I hope to finish in 2023 and then move into the production phase.

Tell us what you think of the interview with Cengiz Akaygun. What do you think of it? What ideas did you get? Do you have any suggestions? Or did it help you? Let’s have your comments below and/or on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter.

Follow Cengiz Akaygun on Social Media

Website

IMDb

LinkedIn

Instagram

Vimeo

MORE STORIES FOR YOU

Richard Green Documentary, ‘I Know Catherine, The Log Lady’: Premiere in NYC, LA May 9th

Lynchian Doc I Know Catherine, The Log Lady Makes Hollywood Premiere 4/17, Rollout to Follow

In Camera by Naqqash Khlalid Launch on VOD April 29

Naqqash Khlalid’s Directs Nabhan Rizwan. In Camera stars an EE BAFTA Rising Star Award Nominee.

2025 Philip K. Dick Sci-Fi Film Festival Award Winners Announced

Vanessa Ly’s Memories of the Future Awarded Best PKD Feature

Dreaming of You by Jack McCafferty Debuts VOD & DVD for April Release

Freestyle Acquires “Dreaming of You” for April 15th Release

Hello Stranger by Paul Raschid set for London Games Festival & BIFFF

The film Is set for an April 10th Premiere at The Genesis Cinema in London (LGF) and BIFFF

Daydreamers Official Trailer by Timothy Linh Bui: Released by Dark Star Pictures

Daydreamers Vietnamese Vampire Thriller – May 2nd release