A Case Study

Narrative | Dramatic Features

Film Name: Language Games

Genre: Absurdism

Date: February 21, 2021

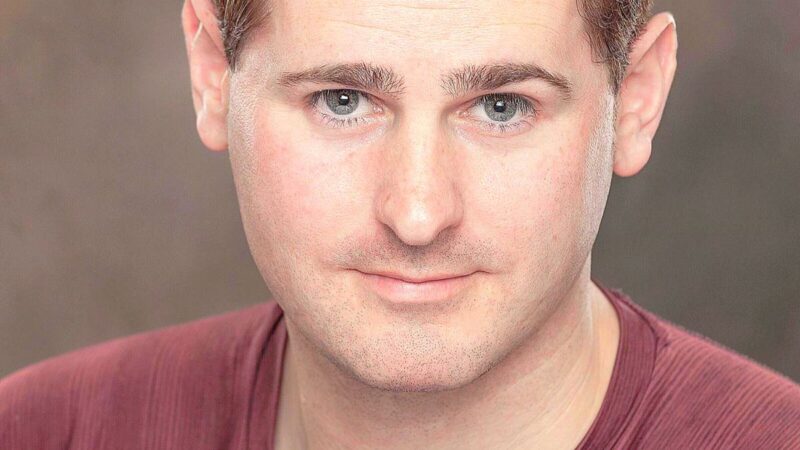

Director: Ralph Lewis

Producer: Ralph Lewis, Catherine Porter, Barry Rowell, and Barbara Yoshida

Writer: Barbara Yoshida

Cinematographer: Barry Rowell

Production Company: Peculiar Works Project

Budget: $17,000

Financing: Donations from friends and Unemployment Insurance

Shooting Format: NA

Screening Format: NA

World Premiere: NA

Awards: NA

Website: www.peculiarworks.org

indieactivity: Tell us about “who you are”?

Ralph Lewis (RL): I am a theater director and one of the 3 producing partners of Peculiar Works Project. We are a site-based creator of multi-disciplinary projects, which just means that we perform weird shit, but not in theaters. We use interior and exterior environments as co-creators, investigating the effects that space and site can have on the development of live theater. Throughout my 30-year career in the NYC Indie Theater community, I’ve executed a few film and digital projects, but this film is the first to make it past post-production and into the distribution stage.

Introduce your film?

Ralph Lewis (RL): Language Games is set in an absurdist world of philosophy and language, where Sheela joins three great thinkers from the past for a spirited game of Mahjong. As they play, her energy conjures Joseph Beuys as a mythological hare. Invisible to the players, he interjects cultural incantations while the players contemplate how language evolved from naming animals to representing them with signs and how myths serve the human need to imagine. Physical chair-play creates an escalating rhythm as tensions build and the hare inspires Sheela to be more confrontational. As the “chair-e-ography” builds to a crescendo, Sheela questions a philosophical theory and wins the game.

It’s shot in a rough-and-ready style that epitomizes the Covid times we are in. It incorporates strong visual elements and ambiguous characters—are they real? It’s a high-energy film that escalates in intensity as it progresses, leading to a dramatic finish.

Tell us why you chose to write, produce, direct, shoot, cut/edit the movie? Was it financial, chance, or no-budget reason?

Ralph Lewis (RL): Before the pandemic, writer Barbara Yoshida had submitted this short play to an NYC theater festival, but by the time it had been selected for presentation, the festival had moved into the virtual space. Rather than do a static Zoom reading of the piece, I chose to film it and began negotiations with SAG-AFTRA.

Introduce your crew?

Ralph Lewis (RL): Because we were shooting this film last fall while Covid had spiked again, we were required to rely on a very small crew who gratefully trusted us with their health and safety. I enlisted some of our nearest and dearest collaborators, including stage manager Heather Olmstead, lighting designer David Castaneda, costume designer Michelle Beshaw, and co-producer Barry Rowell as Director of Photography, and we added Akia Squitieri as our Health Safety Specialist. It’s not the first time these artists trusted us, but it’s the production where trust was the most vital. And no one got sick!

Due to the time constraints, we were under in order to make the deadline for the Festival (mentioned above), I couldn’t schedule enough rehearsals. And as it got further into October, the weather got colder. Throughout the entire process, the actors and crew were real troopers—supportive and professional, often staying longer on the rooftop than planned, and we didn’t hear the slightest grumbling or complaint. I feel extremely lucky to have worked with this cast and crew. They made us proud!

What are your personal experiences putting on all these hats/responsibilities (simultaneously)? Tell us about story, writing, and production?

Ralph Lewis (RL): I learned the most from working with a talented editor after the film was shot. Editing, editing, editing! Now we know why people say that a film is made in the editing room. The theater is the actor’s domain, television is the writer’s, and in film, it’s the director’s, but without a great editor none of that matters. I have a much better idea of what we would do differently while filming the next project.

What is the source of the idea? How did the story develop from the idea? And how did the story evolve into a screenplay? Why do this story? Do you have a writing process?

Ralph Lewis (RL): Language Games is one short play in The Hare Trilogy, written by Barbara Yoshida, and I’ve been working with her throughout the pandemic to create a live-filmed hybrid production that we hope to realize together fully next fall. The development process has taken place with a variety of actors on Zoom, gathering feedback from invited audiences and conceptualizing this work for the new virtual venue that we’re all still just learning about. Barbara has a keen eye for words, both spoken and unspoken, so I’ve just focused on how to allow her story to unfold and connect with audiences in this challenging new context.

As the playwright wrote to me: I have always loved words and languages, and this short play has given me the opportunity to explore gestural and non-linguistic forms of language as well as the philosophy of language; the importance of myth; and the contribution of animals to humankind’s evolution. I turned to Alexander Stern’s The Fall of Language for insight into Wittgenstein’s and Benjamin’s thoughts on immanent and designative language, or name and sign. Since the play views the opacity of some philosophical tenets through the lens of absurdity, I thought it would be amusing and absurd to see these super-intellectual guys playing Mahjong, a game like gin rummy. You’d think they’d be playing chess or bridge, right? Paul Shepard provides a good counterpoint to the philosophers’ conceptual obscurity—his take on the origins of language is so down-to-earth. And then there’s Joseph Beuys: he combines the immanent language of art with mythology. The hare was his animal—he even had a hare as a hood ornament on his car! Sheela probably represents me, always skeptical about “high-falutin’ mumbo-jumbo.” While the play is about language, the content is a very contemporary, feminist, and Absurdist take on the insularity of intellectual posturing and pushback against male dominance. They are playing Mahjong, but there is another kind of game going on, and Sheela rises to the challenge.

Did the tight shooting schedule make it harder or easier? How did it affect performances?

RL: Because this piece had already been chosen for a theater festival, we had a deadline before ever starting. That was very helpful. We had many challenging hurdles from SAG-AFTRA that almost sunk the project, but I finally worked out a deal with them and took on their added Covid protocols. For health safety reasons, I shot on an outdoor roof with the most limited crew possible. We shot everything in just a couple of days with actors working mostly solo, and I hoped we could make it look like they were together around a table in the editing process. Everyone had to be tested in advance, but only 48 hours in advance, so the timing was very, very tight. And we can’t say enough about how important it was to have a Health Safety Specialist on-set to do temperature checks; collect individual affidavits; space out the make-up, costume, and holding areas; make sure everyone was masked and goggled when not rolling; and so much more. After 25 years of making theatre, this was probably the hardest thing I’d ever done in terms of new requirements and limited time & space.

During the film production, what scene (that made the cut) was the hardest to shoot? And why?

RL: Since most of the film was shot one actor at a time, I needed a couple of shots that would establish location and relationships, so we endeavored to shoot 2 takes that panned around their Mahjong table with all actors present. The actors could only be that close together, unmasked, for a short period of time, so we had to get it right and do it quickly. Because it was a circular panning shot, the crew had to move with the camera, staying out of the frameline, so although the actors were staying put, the crew was running in circles at a pace that was beyond difficult and as absurd, and the script itself.

What were the advantages and disadvantages of the way you worked?

RL: Working on a rooftop meant that we had to deal with constantly changing weather and lighting conditions from setup to set up, and even during a single shot—suddenly, a cloud appeared in the middle of shooting a scene that had started in bright sunlight. This meant that we had a lot of work to do during the editing process. A construction crew was building a new building right next door, so there was a lot of noise to deal with during editing, as well. And of course, shooting outdoors meant helicopters, sirens, and honking horns.

When did you form your production company – and what was the original motivation for its formation?

RL: After having been treated poorly as actors with another theater company in 1993, my partners, Catherine Porter and Barry Rowell, and I decided to break out on our own. We wanted to do site-specific theater and we wanted to be multi-disciplinary – Peculiar Works Project was born. Our award-winning company encourages collaboration, experimentation, and a rebel spirit in artists by providing them with the tools and opportunities needed for artistic exploration. We perform in unconventional, non-theater spaces because we believe artistic work wakes up a site, the site, in turn, transforms the work, and audiences then experience both in surprising new ways. Through these unique locations—city streets, landmarked buildings, gutted storefronts, and other peculiar sites throughout NYC and beyond—and unusual performances, Peculiar Works brings diverse communities of artists and audiences together.

How much did you go over budget? How did you manage it?

RL: Everything changed when Covid hit, so all of our plans went out the window, and so did our funding. There was no way to write grants and have them funded in time to continue working, so we’ve made donations to our own company. Basically, we paid for it out of our own pockets. Because of the SAG-AFTRA contract, we paid all of the actors at scale, so we paid the crew the same amount, and the same for ourselves as producers. From start to finish, the film cost about $17,000, which is more than we usually pay for a short piece, but it was well worth it.

What else have you got in the works?

RL: We are already working on the next two short plays in The Hare Trilogy, but it will take some new ways of raising funds, so there’s a lot of administrative work going on already. Yes, we do all that ourselves, too. And we’ve begun pre-planning for a return to live performance with an adaptation of poet Diane DiPrima’s play, Monuments. It was the last play performed at the legendary Caffe Cino. Diane was a friend of the Company from 2007 until she passed away last year, so this will be a celebration of her life, performed outdoors in a traveling show to some hotspots in NYC’s West Village.

Tell us what you think of the Case Study for the name of the film What do you think of it? Let’s have your comments below and/or on Facebook or Instagram! Or join me on Twitter.

Follow Ralph Lewis on Social Media

Website

IMDb

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

MORE STORIES FOR YOU